Newsletter / Research Activity Report / Miho Fuyama

RARA Newsletter vol. 4 “Indeterminacy” is Often Lost in Modern Society. I Wish to Explain and Convey its Value: Interview with Associate Fellow Miho Fuyama

2024 / 04 / 12

2024 / 04 / 12

RARA Newsletter vol. 4

“Indeterminacy” is Often Lost in Modern Society. I Wish to Explain and Convey its Value: Interview with Associate Fellow Miho Fuyama

We are pleased to share an interview with RARA Associate Fellow Miho Fuyama, an Associate Professor at the College of Letters.

Assoc. Prof. Fuyama specializes in cognitive science, and her topic of research is “Indeterminate Cognitive State and Its Effect on Literature and Art: The Possibility of Indeterminacy ”. Here, “indeterminacy” refers to the uncertainty (as a value) in the state of cognition.

Her research on indeterminacy has been selected for the Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (CREST*) program under the Japan Science and Technology Agency and she is involved in joint research with researchers from overseas universities.

In an era characterized by terms like “cost-effectiveness” and “time efficiency,” having fixed or easy-to-understand concepts is a priority. However, Assoc. Prof. Fuyama is studying the state of being undecided, that is, of “indeterminacy.”

Why did Assoc. Prof. Fuyama begin researching this topic? What are the states of indeterminacy, what texts and works of art arise from them, and what subjective experiences do they bring? She also discusses her career and the possibility of a quantum theoretical approach.

*CREST: Team-oriented research initiative aimed at promoting original and internationally high-standard basic research, achieving strategic goals set by the government, and producing outstanding research results that will contribute to future scientific and technological innovation.

(The following is a summary of the conversation with Assoc. Prof. Fuyama)

Does “Indeterminacy” Create Aesthetic Experiences and Creativity?

This modern era is represented by terms such as “cost-effectiveness” and “time efficiency,” and the value system of “immediate decision-making| and “immediate understanding” is becoming more widespread. My research is the opposite of this. I wish to explore a new view of humanity by focusing on the possibility of uncertainty, namely, of “undecidedness” or “indeterminacy.”

A simple example I give when explaining this is my favorite novel Manazuru by Hiromi Kawakami, where the protagonist meets her deceased husband. When her supposedly dead husband asks her, “Are you coming here?” she responds by saying, “Ikitai.”

The Japanese word “Ikitai” can be interpreted as “I want to go (there)” or “I want to live.” It has a double meaning and the meanings contradict each other. The reader does not know which word the protagonist meant.

I think that the inherent aesthetic experience born from this uncertainty in perception creates a sense of immersion. The experience brought about by this kind of “indeterminacy” has long been studied in the humanities.

The ability to make decisions and solve problems quickly is highly valued in modern society and business, but the concept of “negative capability” proposed by the English poet John Keats has also been attracting attention in recent years. Discussing Shakespeare’s creativity, Keats defined negative capability as “being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason” (Keats, 1817/1891 Translated by Sato 1952, p. 65), and suggested that this was the root of his creativity.

Other research, such as Umberto Eco’s The Open Work or Wolfgang Iser’s The Reading Process: A Phenomenological Approach, has noted that there are parts of novels and contemporary art that are open to interpretation on the part of the reader/viewer and that the fact that everything is not necessarily determined creates an aesthetic experience and sense of immersion.

I Want to Scientifically Clarify the Value of “Indeterminacy”

Although the concept of “indeterminacy” in cognition has long attracted attention in the humanities, it has not been examined scientifically. Now that the worth of indeterminacy is being lost in modern society, my goal is to scientifically explain its mechanisms and possibilities through interdisciplinary research in cognitive science, neuroscience, and mathematics.

My specific objective is to be able to explain and promote “indeterminate” cognitive states in our understanding of literature and art.

I hypothesize that if we always prioritize “understanding” and “fixing” in the short term, we will only achieve local optimization and short-term understanding. However, it is only by enduring unknowability to a certain extent or by enjoying that state of unknowability that we can achieve true understanding and encourage creativity.

Moreover, Eco and Iser, as mentioned earlier, argue that immersion and aesthetic sensations can come from indeterminacy “openness” or “emptiness.” If this is true, I believe that by implementing “indeterminacy” in virtual reality (VR), we can effectively enhance aesthetic sensations in the real world. This is the world we picture beyond our research.

From Classical Probability Theory to Quantum Probability Theory

While we have mainly discussed topics that have been the focus of research in the humanities to this point, I am trying to use the framework of quantum cognition to explain this. Cognitive science is a discipline that seeks to understand the function and nature of human knowledge from the perspective of information processing. The term “quantum cognition” may sound like it belongs in physics, but it refers to cognitive research using mathematics called “quantum probability theory” (noncommutative probability theory).

Although many existing cognitive studies carry out modeling based on the classical probability theory, it is a narrower theory than quantum probability theory, and we know there are cognitive phenomena that it cannot explain.

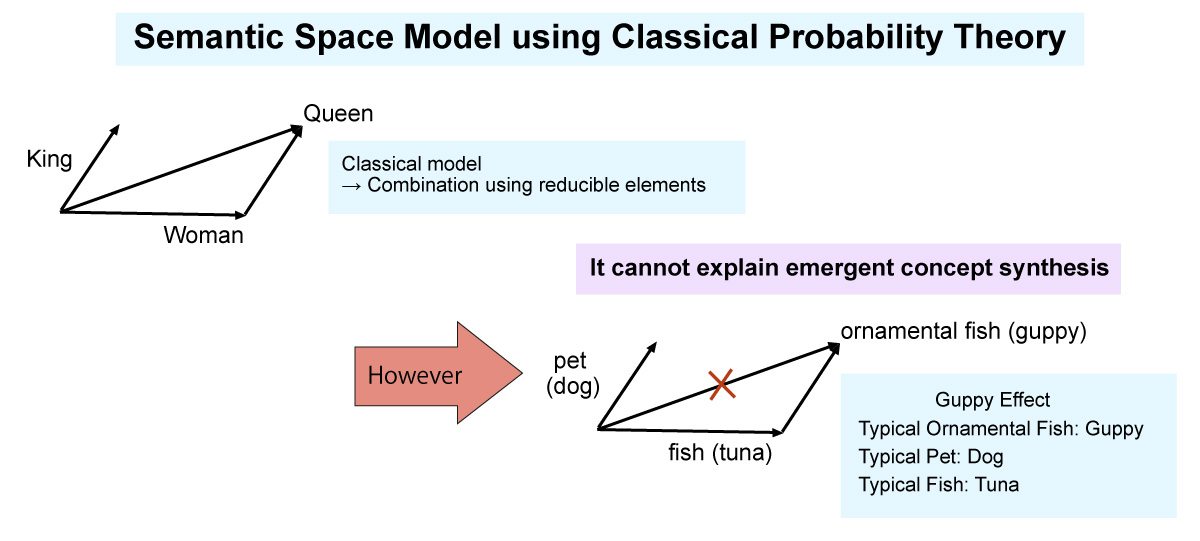

Word2Vec (Word to Vector) is an example of a highly interpretable semantic space model using classical probability theory. When the words “woman” and “king” are expressed as vectors and added together, they become “queen.” However, classical probability theory cannot explain the “guppy effect.” When a pet, such as a dog, is combined with a fish, such as a tuna, you will get an ornamental fish; however, the guppy, which is a typical example of an ornamental fish, is not high on the list of examples of dogs or fishes. This concept is known as an emergent concept synthesis. The guppy effect cannot be explained by a semantic space model using a vector space.

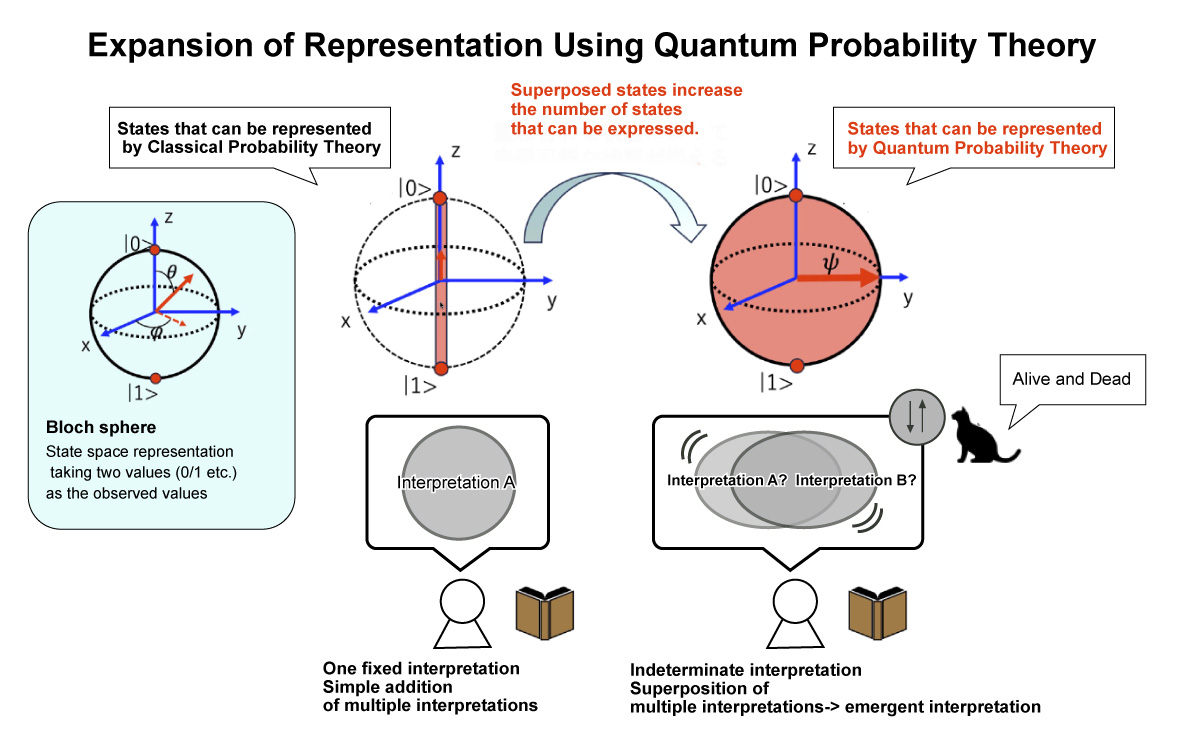

To explain phenomena that classical probability theory models cannot explain, I am advancing the mathematical modeling of cognition using quantum probability theory. I believe that this will help explain and predict cognition, which has been difficult to clarify using conventional classical probability theory, more accurately and with greater freedom.

We can represent the comparison of states using the Bloch sphere, a type of state space, as an example. The axis of the sphere (red part of the sphere on the left) is the part of the state that can be represented by classical probability theory, while quantum probability theory can represent the whole sphere including the interior (red part of the sphere on the right). Quantum probability theory can express a special state that cannot be represented by classical probability theory, an emergent representation of the “superposition” state of multiple interpretations.

Cognitive states that can be modeled by quantum probability theory are called quantum cognitive states. It may be possible to model “emergent interpretation states” that go beyond just adding multiple interpretations using superposition states that are unique to quantum probability theory. In particular, I want to model the state of indeterminacy that occurs when people engage with literary or artistic works. For example, I am theoretically and experimentally studying the superposition of “alive” and “dead” and the cognitive effects arising from the fact that there is no settled interpretation of them.

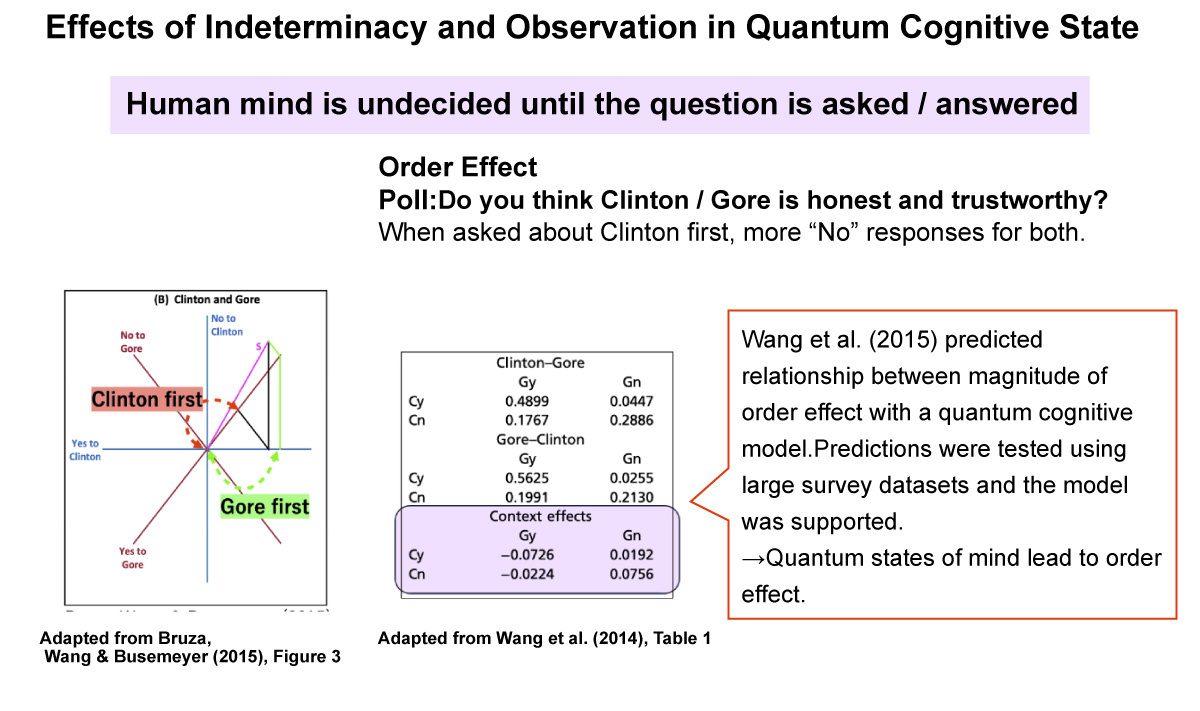

One well-known example of undecidedness is the order effect. There was a famous experiment in which respondents were asked two questions in different orders: “Do you think Clinton is honest and trustworthy?” and “Do you think Gore is honest and trustworthy?”

If the question about Clinton was asked first, more people tended to respond that both were untrustworthy compared to when the question about Gore was asked first. This shows how our minds are not always settled until they are observed.

Example of the order effect. We can see that the results of the poll are affected by the sequence of the questions.

Until now, it was difficult to provide a mathematical explanation of the order effect, but my research collaborators suggest that quantum probability theory might help us explain it.

According to the quantum probability theory, our opinions are not set before we are surveyed, and our answer is undetermined before we are asked a question. The theory allows for an opinion to be in an indefinite state before being asked a question, with the answer only being determined when the question is asked. Therefore, it is said that the way observations are conducted can influence responses and reveal underlying uncertainties.

This kind of observation effect has been noted in psychology, but I think most research has been limited to qualitative explanations such as heuristics and biases, with relatively little attention to indeterminacy itself.

Research on quantum cognition using quantum probabilities has gradually spread across the world in recent years, especially since the publication of Quantum Models of Cognition and Decision in 2012.

The authors, Prof. Jerome R. Busemeyer and Prof. Peter D. Bruza, are also part of our collaborative research. Prof. Andrei Khrennikov, who has been a pioneer in quantum cognition research, was a keynote speaker at a workshop held at Ritsumeikan University last November. He will remain involved in this research going forward.

Front row, center: Prof. Peter D. Bruza. To the left of the center is Assoc. Prof. Fuyama.

The tall man in the center is Prof. Andrei Khrennikov. Next to him is Assoc. Prof. Fuyama.

We have three specific goals:

a) Mapping external stimuli that trigger quantum cognitive states and their effects (reality, immersion, emotion).

b) Establishing methods for observing quantum cognitive states.

c) Modeling transitions and observations of cognitive states using quantum probability theory.

We have a team working on each of these goals. We will work with neuroscientists, mathematicians, and cognitive scientists to construct methods to observe quantum cognitive states that have not yet been established, build advanced mathematical models that can express quantum cognitive states including unsteady temporal changes, and investigate what kinds of texts and works of art make us “uncertain” and what kinds of aesthetic and immersive experiences they cause.

A lot of traditional Japanese art focuses on indeterminacy. In the future, I would like to examine the cognitive states and effects of this art, conduct workshops with our fellow researchers to make people feel “indeterminate” and develop VR and AR technologies as mentioned earlier. The humanities suggest that hope lies in indeterminacy, so I would like to consider this topic together with researchers in that field.

A Unique Career Guided by an Approach Combining Literature, Cognitive Science, and Quantum Mechanics

I have been investigating text comprehension since I started my research in the field of cognitive science. A lot of cognitive and psychological research hypothesizes that readers always choose the most plausible interpretation at any given point in time.

However, at every point, they settle on and hold onto one fixed interpretation. I think this hypothesis is not evident in practice. I found no reason to hold onto one interpretation throughout the reading of a text. For example, in Manazuru, one can interpret the story in a way that does not settle on either “living” or “dying.”

Further, I think that the aesthetic experience is created because the exact opposite interpretations are mixed. This is the point on which I disagreed with previous models, and what led me to this research.

My career is a little unusual. First, I completed a master’s degree in physics at Kyoto University’s Graduate School of Science. I then worked for a company for about three years, before starting a master’s degree program in Japanese Studies at Osaka University’s School of Letters. I then moved into the field of cognitive science.

My background in hermeneutics and semiotics, which I studied at the School of Letters, made me uncomfortable about my research on text comprehension in the field of cognitive science. Along with this discomfort, I was also aware of quantum physics, so I felt that it should be viewed as “multiple interpretations mixed together, a quantum superposition state rather than a classical weighted sum of probabilities.”

When I mentioned this to my research peers, I was introduced to quantum cognition research overseas, which brought me to my current subject. I conceived the idea around 2018 and started my research on it in 2020.

Interacting with students, it feels like they think “There should be one fixed answer,” “I should find out by searching for it or using AI generation,” and “I want to decide without worrying about it.” I hope to convey the message to the students that there is something interesting in being in a state of ‘not deciding’ or ‘being undetermined’.

For example, I think everyone has “spare time.” We think we need to do something efficiently to make use of that “spare time,” but why not let it be undecided? You can relax, look at something beautiful, or spend time on something that you do not know will be useful. I think you will be able to experience the charm of “indeterminacy” in this way.

My own career seems to have taken a circuitous route across the humanities and sciences, but I feel that sometimes things that you do not know are useful actually end up being useful in the long run. When I started working in the private sector, I never thought I would go back to physics again, but ten years later, I started to think, “Oh, maybe…” and my physics-related knowledge is what led me to this research.

If you only do the things that are useful at the moment, you will not be able to expand your abilities to something that may someday prove useful unexpectedly. Experiencing things that may or may not be useful during your spare time can be a fun, immersive, and aesthetic experience in itself, and it might just lead to something new. I want to clarify the appeal of such indeterminacy in the hope that more researchers focus on it in the future.

Through RARA and CREST, I Want to Work with a Diverse Range of Researchers to Spread Information

We intend to disseminate information in various ways in the future, including collaborating with other researchers on special features in academic journals and international workshops.

For example, we are conducting joint research on the relationship between uncertainty and adversity with Dr. Makiko Yamada of the National Institutes for Quantum and Radiological Science and Technology, who has been working on adversity as part of the Moonshot R&D Program. We are planning a special issue in an academic journal. I believe that indeterminacy will show its value in adverse situations, and I hope this will lead to developments in cooperation with multiple fields that find hope in indeterminacy.

Since the project was taken up by CREST, we have attracted the interest of people in related fields. However, the field of quantum cognition is still not very active in Japan. Discussing the concept of indeterminacy is primarily an interest of the humanities, and the barrier to this discussion in terms of quantum probability seems to be very high. I want to increase the number of people interested in the field, including non-researchers, by communicating and spreading awareness.

I think it is interesting to be able to interact with professors at RARA who are in different fields and employ different styles than I do. Professors are working on industry–academia collaboration, education, and research at various levels, and I would be happy to learn what other researchers are thinking about and how they are advancing their research and disseminating this information together across disciplines.